The full 2024 Republican Party Platform was released and adopted earlier this month at the 2024 Republican National Convention. The platform devotes a chapter to education (“Cultivate Great K-12 Schools Leading to Great Jobs and Great Lives for Young People”), which focuses on issues like parental rights, career preparation, and a call for universal school choice.

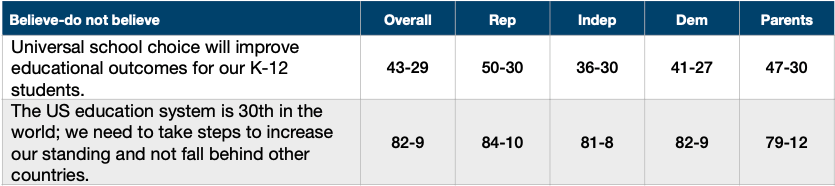

The natural next question is what impact voters think universal school choice would have on K-12 education. Data from the latest survey for Winning the Issues (July 23-25), shows that, while voters believe universal school choice will improve educational outcomes for our K-12 students, it a plurality rather than a majority (43-29 believe-do not believe). Parents come closer to a majority (47-30), compared to Democrats (41-27) and especially independents (36-30). Republicans have the highest level of belief, but even then it is only one in two (50-30) for this plank of the party’s educational platform.

Voters were also asked to react to a second statement on education, this one adapted from a speech given at the convention: “In 2016, many people began to doubt the promise of America. … Our standing on the world stage was weak at best. … Our educational system was broken, ranked 30th in the world.”

Overall, 82% believed that the US education system is 30th in the world and that we need to take steps to increase our standing and not fall behind other countries (82-9). This statement had strong, bipartisan levels of belief (84-10 among Republicans; 81-8 among independents; 82-9 among Democrats), and a high level of belief among parents (79-12).

Clearly, voters understand that the US has improvements it could make when it comes to education.