Over the weekend, hundreds of top scientists and mathematicians released a statement to, as they wrote, “express our alarm over recent trends in K-12 mathematics education in the United States.” Citing the California Mathematics Framework as an example of such a reform that is intended to enhance equity and reduce disparities, the authors go on to criticize these efforts and their consequences. As they conclude their letter, “Reducing access to advanced mathematics and elevating trendy but shallow courses over foundational skills would cause lasting damage to STEM education in the country.”

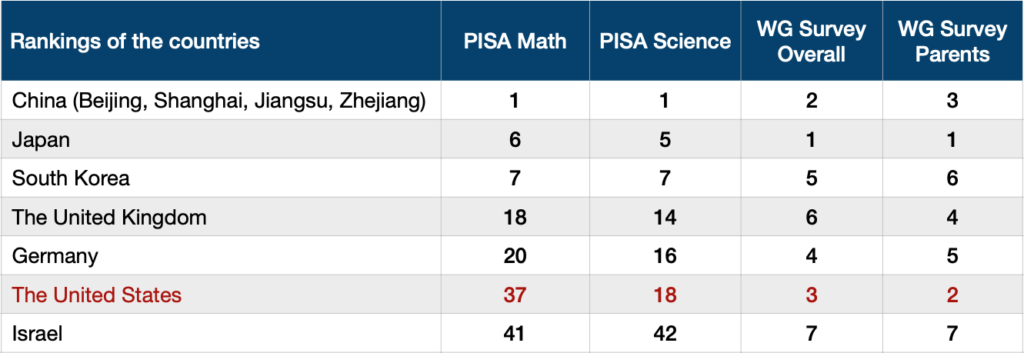

Among their many criticisms of these reforms is that they will put US students at a disadvantage compared to their international peers in math. These concerns are not misplaced. As we have noted in previous posts, the US ranked 37th in math, 18th in science, and 13th in reading on the most recent (2018) PISA tests, far from the top. But data from the most recent survey for Winning the Issues (November 22-24; 1,000 registered voters) suggest that voters do not appreciate where US students actually stand compared to their international peers.

Presented with a list of 7 countries — the US, China, South Korea, the UK, Germany, Japan, and Israel — and asked to rank to each based on how highly they thought that country’s students achieve academically, Japan comes in first. China is second, and the US is third. Overall, 28% of voters assigned the US to the top slot. Parents were even more likely to rate the US more highly, putting it second behind Japan and ahead of China.

As we have also noted before, when people are told how the US ranks on PISA, they are much more likely to call this a poor or failing performance (rather than good, excellent, or satisfactory) and overwhelmingly agree with the statement that “the US is becoming the world’s ‘C’ student” (70-15 agree-disagree). But in the absence of evidence to the contrary, American voters are likely to overestimate the US’ standing by a considerable margin.